The Milford Sounds area, while a major tourist attraction for New Zealand, is by no means an overpopulated area. There is one town, Te Anau, which has a population of 1785. A single road leads out of Te Anau and into the sounds. The Te Anau - Milford Highway is 120K long and takes you to the most inland point of Milford Sound. There, a small but attractive booking station offers a variety of cruises out on the sounds. Cory and I had mentioned when we were there with Mom and Dad that there was no souvenir shop and no food counter, even though these would surely rake in the cash. It is another major difference in how New Zealand chooses to manage its natural resources. But, as the teachers at school might say, I’ve lost the plot. Back to the point…

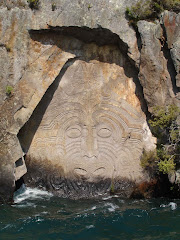

On our trip around the South Island with Mom and Dad we had cruised in the Milford Sound and really loved it. Cory and I knew that we would be back to walk the Milford Track. The Milford Track is a 33.5 mile walk in towards the sound. Because of its popularity, the Department of Conservation (DOC) handles booking requests and limits the number of trampers (aka, hikers) to 40. The DOC, as it does all over New Zealand, maintains a number of huts where trampers stay the night. The DOC hut system is a really fantastic system, with huts (some with fewer services) throughout both islands on well-known and much less well-known tracks. The huts on the Milford offered bunks with mattresses, cold running water, flush toilets, and gas cooking facilities. This all meant that we didn’t need to carry sleeping bag pads or the gas stove, leaving more space for the water filter, four days of food, cooking utensils, clothes, a few toiletries, first aid kits, etc. Each hut also boasted a small helicopter landing pad, which was used occasionally to drop supplies, but more often to offer emergency airlift services. Yikes.

Along with the 40 of us trampers who had booked through the DOC, a “guided tramping service” is also available. These folks pay good money, but the benefits are great. We often envied them when we ran into them on the track. They stay in private huts with flasher amenities (like a hot shower, or, really just any shower at all), have their meals prepared for them, and carry only the clothes they need for the walk in their pack. (This leaves them carrying something bigger than a regular back pack, but much, much smaller than the 17K or 38 lb. pack I had.)

During the summer’s busy season, trampers must walk a prescribed route with set distances each day. Our first day’s walk was very short – only 5k (3.1 miles). The second and third days were 16.5k (10 miles) and 14k (8.7 miles), respectively. The final day was to be 18k (11 miles). Since New Zealand has converted to metric, they use kilometers in their publications about the track, but the original track was cut and marked when miles were used; there are still markers at every mile.

We were scheduled to walk from Wednesday to Saturday. Tuesday night we checked into Keiko’s Bed and Breakfast. Keiko, a Kiwi who is originally from Japan, was not home, but Kevin, her husband and a former guide on the Milford was. We chatted, shared a glass of wine, and quizzed him about the track. Later we ate a meal in an Italian restaurant in Te Anau and went to bed early.

Wednesday morning, we woke up to gray skies and rain. Rain is sort of a given on the Milford Track, an area that averages between 6 and 9 meters a year. After a quick breakfast and many well-wishes from Kevin, we headed down to the Te Anau DOC office. Before you can start the track, you’ve got to get there, so we boarded a bus. The bus took us into to Te Anau Downs, a small settlement that offers a boating ramp and a lodge. Here we loaded onto a boat and cruised up the Clinton arm of Lake Te Anau. We got off the boat at Glade Wharf, where we would begin our day’s walk.

Everyone pulled on their rain gear, hoisted their packs on to their backs, and shoved off. Even with the rain coming down, the setting was gorgeous. We crossed the first of the nine suspension bridges on the track, wandered along the Clinton River, took a side trip to explore a bog area, and arrived at the first hut at about 2 in the afternoon. Each hut on the track was a little different, but all had 2 or more bunk rooms and a good-sized cooking facility. We hung up our rain gear, claimed two bunks, and got out some food for lunch. We ate a quick meal outside, but the sandflies (small black flies that leave terribly itchy bites) chased us back inside. After a dozen hands of rummy (the only card game we could remember the rules to) and a few chapters in our books, it was 5:00. The hut ranger was leading a little nature walk, so we bravely pulled on our rain gear and headed out with him.

I’m pretty unclear about what exactly a DOC ranger’s day-to-day life must be like, but I’d really like to know more. The Milford huts are only staffed during the summer, so the rangers must be assigned someplace else during the winter. During the summer, they live in a small, private hut near the other buildings. Each of the rangers we met were men and appeared to have no family with them. (I assume they couldn’t really have school-aged children on the track, because there was no way for a child to get to school. They’d have to walk out, hop on a boat, then catch a ride into Te Anau – a daily commute like this would take a minimum of 6 hours a day!) Our last ranger mentioned that that morning he’d been doing track maintenance a few kilometers up the track. We saw evidence of it that next morning after about 8 kilometers. Because the track doesn’t cater to vehicles of any kind, he must have spent the day walking to the worksite, completing the necessary tasks, and then walking home. But, even after the physical work and the long walking, his day wasn’t done. At night, rangers do a brief “hut talk”, informing trampers of what the next day’s route looks like, updating weather forecasts, and dealing with any inquiries. They also monitor the incoming trampers, so that when night falls, they have a head count for who has arrived. The ranger at our last hut, the most talkative of the three, told us some stories of not-so-bright trampers and the search attempts made on their behalf, another important role of the Milford Track rangers.

Our nature walk was excellent, though we were glad to once again pull off our rain gear and get ready for dinner. We entered into the warm cooking facility, where all most all of the 40 trampers had gathered. Most of us were walking with someone else, but there were a few people walking solo (2 women and 3 men) and a few walking in groups of four. All in all, there were seven young Americans, ten young Israelis, one young man from Holland, three young woman from places unknown, and about twenty 40-65 year olds from Australia and New Zealand. It was an interesting mix of youngish “foreigners” and older “locals”. But everyone was helpful, sharing food, advice, and in my case, band-aids.

Our first night we dined on gooey pasta and, for dessert, hot cocoa. After dinner, we struck up a conversation with two couples traveling together. One couple was from Guam and the other from Saipan. They were young Americans and had been traveling around NZ for several weeks. Three of them were dentists; the fourth was a dental hygienist. We talked dentistry and orthopaedics until the solar-powered lights shut off that night. It was clearly meant to be…

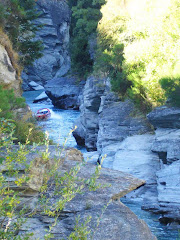

We woke up the next morning and headed off before the rain began. In fact, we got a good two hours in before the rain started. But, as you must cheerfully remind yourself when walking the Milford, more rain means more waterfalls. We walked through a steep-sided valley, with high-up waterfalls cascading down. In the winter, the area boasts 56 known avalanche paths, which is why we were doing this in summer. The rain began shortly before we sat down for lunch by a lake fed by a roaring waterfall. The day’s walk was a gentle uphill climb of 16.5k, and we were not quite half-way there.

Because of the rain, we had to stop and remind ourselves to take a look around. The hood on my rain gear pretty much takes care of any peripheral vision and I sort of need to concentrate on where I’m putting my feet, so I often found myself keeping a close eye on the track and missing out on the surroundings. But as we settled into a pace, it was easier to remember to appreciate the views.

We slogged into our hut that night, damp and worn out. Though it was not the longest day of the walk, the insipient uphill climb was tiring, and I’d managed to get large blisters on the back of both heels. Our feet were aching, too; others had the same complaint. During one of the hut talks, a ranger helpfully pointed out that on a scale of hardness from one to ten, with the hardness of diamonds scoring a ten, the rocks of this area were an eight. It did sort of explain the throbbing of our feet…

As we pulled off our gear on the porch of the hut, there were large signs saying that all gear needed to be hung up as there were “keas operating in the area”! You might remember these cheeky alpine parrots from an earlier posting. They are an attractive green and red parrot, and they love to explore. One rule at almost all DOC huts everywhere is that you remove tramping boots before entering; here though, we were told to bring our boots inside so that the keas wouldn’t dismantle them overnight. Their antics were a welcome spot of humor that night.

Trampers drifted in that night, hanging wet gear up near the wood-burning stove, changing into dry clothes, and swapping stories of the day’s walk. We sat down with our friends from Guam and Saipan and discussed the need for the DOC to offer massage services at each hut. (We figured the guided walkers probably all ready had that!) A few hands of rummy and a pleasant meal of noodles, canned chicken, and ibuprofen topped off the night. The next day was to be a shorter walk than day two, but we were crossing Mackinnon’s Pass, which meant a steep climb and a long downhill journey to our next hut.

A brochure provided by the DOC when you register to walk the Milford helpfully gives you a basic aerial view and a detailed verbal description of each day’s tramp. It also provides a cut away view of the track, demonstrating the change in altitude that the track covers. Frighteningly, most of that change in altitude seemed to occur all in day three’s walk. We would climb about 500 meters and drop about 950 meters. Because of the uphill and downhill, even though we covered only 14k, our walk was scheduled to take about seven hours (we’d covered 16k in six hours on day two).

The good news for me was that the uphill was only to take about two hours; I really hate uphill. The bad news for Cory was that the downhill was to take the next five hours; he really hates downhill. As we began our climb that morning, blisters freshly bandaged, stomachs full of oatmeal and apples, the sun was shining. It was a welcome change and would make the long day much better.

Our climb up was difficult, but not nearly as difficult as some other climbs we’ve done. (Remember Manuoha Hut in the Waikaremoana area – six hours of clambering uphill?) We ran into several guided walkers and I did envy their light load as they passed us. We also ran into one of their guides. We heard someone approaching very rapidly from behind. As we stepped off to the side, she marched passed us, saying cheerily “I hate uphills!” She was literally bounding from rock to rock, practically running. As a guide, she carried a full-sized pack on her back to, identical, in fact, to the one I was carrying. I was not bounding from rock to rock, however, and no one could claim that I was almost running. Clearly, she was in a league of her own. Having said this, the older trampers in our group were also keeping pace. Cory and I commented numerous times on how the 55-65 year olds were definitely hanging in there; they seemed especially to relish the more challenging parts of the track, like the day’s uphill climb.

The switchbacks tightened as we neared the top of the pass. The views were wonderful and the sky had remained clear. Up on the pass, we stopped near the memorial cairn for old Mackinnon. He was the first guide on the Milford and was known to be a pretty stalwart character. Just beyond the cairn was the “twelve second drop”, where we peered over the edge cautiously. At 1073 meters, we could look over the area we’d walked through the previous day and could see where we were headed for that evening. Twelve seconds is the time it would take, supposedly, until you hit the bottom if you were to take a mistaken step off the cliff, unless of course, you found a ledge to bounce off first.

After a few photos, we walked along the ridge to the shelter on the top of the pass. The building had been blown away four times, but we were pretty sure that today wouldn’t be the fifth. We dropped our packs and celebrated the climb with a big bowl of hot miso soup. I also took the opportunity to check my blisters. As I peeled off my socks and pulled up my long underwear, my skin actually steamed in the cold air; it also stunk. The bandages had slid down and were now sort of just making new blisters. Luckily three Kiwi ladies descended on me with advice and more blister protection than one girl could need. I applied new bandages, and we prepared to set off.

The downhill climb, while long, was very scenic. We began a series of switchbacks down the other side of the pass. Occasionally, we’d see a sign saying “Avalanche area – do not stop for 300 meters.” Eventually, there would be another sign indicating that it was safe to stop. People do walk the Milford track in winter; they are obviously crazy. Then, for almost an hour, we walked alongside a series of waterfalls. (Thank goodness for all that rain the past few days, huh?!) The pooling water was a stunning blue, and the falls cascaded down and down.

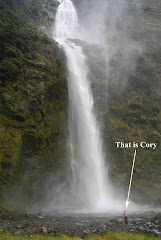

After we left the series of waterfalls, we set our sights upon Sutherland Falls. These three-tiered falls are the largest falls in New Zealand, and there was a short detour off the track to the falls; we’d been told not to miss them. It was at this point that I began to try and figure how much more we had to go. I spent a lot of time converting kilometers to miles, then figuring out my pace, and then converting back to kilometers. Often I’d forget a number that I’d converted and have to start again. Then I’d recheck my math a few times. Anything to quiet my annoying inner monologue!

Later, as we sat to have a break and a snack, our friends from Guam passed us. “Let us know with a whistle or something”, we said, “when you get to the 20 mile mark near the Sutherland Falls.” As we walked on, not ten minutes later, we heard a whistle, then a holler, then a cheer. They were probably the most glorious noises of the trip. Our strides lengthened, our pace increased. We were so pleased to drop our packs at the little shelter 45 minutes from the falls. We rubbed our shoulders and stretched out our backs. The little side walk without a pack would be a very welcome break.

We headed into Sutherland, running into more and more of our fellow trampers. Everyone looked exhausted, but knowing that we’d done the most difficult section seemed to elevate everyone’s spirits.

The falls themselves were wondrous. The top, 580 meters up, was barely discernible. Cory had decided he wanted to walk in behind the falls, so we once again shrugged into our rain gear. Water blew everywhere as we waded across the pool; we stumbled over rocks, the water and blowing spray making it hard to see. Finally, we stopped to look around. All I could see was water and spray on all sides; we were behind the falls, water crashing down around us.

As we made our way out, I pulled the hood of my rain gear down and massaged my scalp. I figured this was probably the closest to a shower I was going to get, and my hair was starting to style itself. We walked back to the shelter where we’d dropped our packs, had a snack, and continued on. The falls had been at mile 20, and the hut was at mile 22. These last two miles, though, took us right around an hour to walk. Cory’s knees were not feeling great and my blisters made a little complaint with each step.

That night we treated ourselves to a fancy dehydrated meal – tikka masala. It was good, but I wished we’d picked up the strawberry ice cream dehydrated dessert instead! Oh well! The next morning was to be an early one, as we needed to walk our longest distance yet, 18k, to meet the boat that was taking us out of the sound at 2 p.m. We definitely didn’t want to miss that boat!

After our last breakfast of oatmeal and apples the next morning, my blister-bandage fairy provided me with two more large bandages for my heels. Appropriately geared up, we headed off. Before long, we passed by the attractive Mackay Falls. A little Milford Track history for you…While Mackinnon cut the track from his namesake pass out to Lake Te Anau, Mackay and Sutherland cut the northeastern half of the trail, starting at the sound and working inland towards the pass. The story goes that when they stumbled on the first set of impressive falls, they flipped a coin to see who would name them. Mackay won, and the beautiful little Mackay falls got its European name. Sutherland was disappointed, but knew he would get to name the next falls they passed, thus he earned the right to give New Zealand’s largest falls his name. Maybe losing that toss wasn’t so bad after all.

We carried on, acutely aware of the time. It was another sunny day, and I’d even been so daring as to put my rain coat and pack cover in my pack. I knew better than to tempt the Fates, so I did wear my rain pants. (Should it start to rain, it is way too much work to take off gaiters and boots to put on rain pants before putting gaiters and boots back on. At that point, you may as well just get wet.) Since many of us were on the 2:00 p.m. boat, most of us had taken off about the same time. We exchanged pleasantries as we passed, and a large group of us settled at a small shelter for lunch together. Here we met up with our friends from Guam and Saipan and did the last three and a half miles together.

By this point, I was watching out for mile markers like a nervous drug dealer might scan for police. I wanted it to be over. Luckily, the company was a good distraction and the 2:00 deadline was a good motivator. Then, suddenly, with a cry from the front of the pack, we were there. At a small shelter, a few of our fellow walkers were sprawled out. Without a moment’s hesitation, I peeled off gaiters, boots, socks, and rain pants. The sandflies, too, without a moment’s hesitation, located us. So after painting on more bug spray, we took a gander around us. A small path led from the shelter to a wharf. A sign indicated that we had completed the Milford Track, all 33.5 miles of it.

I do realize that 33.5 miles doesn’t really sound all that impressive. In fact, by the third day, as we were at our most tired, we hadn’t even done the equivalent of a marathon yet. Feeling acutely weak, we tried listing the challenges we faced: the elevation changes were significant, the pack on our back was heavy, the terrain underfoot was uneven at best. Then we remembered all the ultra marathoners and the runners that crossed mountains and more… We decided the people that do those are just crazy and had to leave it at that.

So we celebrated our 33.5 anyway. The sign was a reward in itself. It boldly proclaimed the miles and was hung about with worn out tramping boots. Some were barely in one piece, with soles that were taped together, and some looked perfectly fine, as though their owners had simply hung up their boots both literally and figuratively. Someone had the bright idea to take a picture with the sign in the background as we jumped to show our delight. I wasn’t sure I’d be able to jump; I imagine my calf muscles cramping up so significantly that I would crash to the ground upon landing. But we did the requisite “jumping with delight” picture, and I even managed to get off the ground.

It wasn’t a long wait for the boat to arrive, but we were faced with the unappealing news that we had just a little further to walk. The water was low and the boat had to dock at a point some 400 meters further along. Most of us had replaced our boots with sandals, and being too lazy to even strap on my pack properly, we wobbled across a few more steps of rocky terrain. Many made jokes about this last little distance - surely, the guided walkers would not have had to walk clear out here!

We crammed onto the boat, loading up dirty packs, stinking boots, and exhausted trampers. Almost everyone sat outside, enjoying the short ride through Milford Sound. We unloaded, said our goodbyes to our new friends, and boarded a bus back to Te Anau.

We dined that night in the same Italian restaurant that we’d eaten in earlier. Both of us finished every bite of our meal and did so quickly. Cory, who usually helps moderate my excessive eating, let me get my own dessert, but I couldn’t even finish it – it was the richest, sweetest thing I’d had in so many days.

We slept well that night, needless to say, and awoke to catch our plane the next morning. We exchanged stories with Kevin, our host, over breakfast, then limped to our car to drive to the airport.

We laughed at ourselves all day, as any change from sitting to standing took some time, and walking was more like shuffling. We sat in the $2 massage chairs at the airport and enjoyed all four minutes of it.

As we deplaned in Tauranga, the heat rose off the asphalt to greet us. It was good to be home.

Saturday, March 28, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Sounds like a very memorable tramp, something that will become one of your fondest memories. Much like one of our fondest memories which was the birth of our youngest exactly 32 years ago today.

Happy Birthday Cory!

Love, Mom and Dad "C"

Post a Comment