I talked Cory into signing up for a Maori language and culture class with me at Otumoetai College, the regular education high school where I’m volunteering. The colleges here offer a broad range of vocational skills training, making their campuses a great place for a variety of continuing ed classes, from financial planning to gluten-free cooking to beginning guitar.

We meet on Wednesday evenings for about two hours; so far we’ve had three classes and are loving it! Our instructor, Ihaka, is the instructor for Te Reo Maori (“the Maori language”) at the college and he is really good. I was pretty worried on the first night – I didn’t know how far behind the other students we would be. I thought that everyone else would have pretty good pronunciation skills and would be working on their conversational skills. Luckily for us, it has turned out that we are in pretty much the same boat as the other 7 students.

At first I was really surprised by our classmates’ general lack of knowledge of Maori. The students in both the special education placements I volunteer at use some of the language – both in song and in basic nouns and commands. I assumed then that adults who were not disabled would have a much better grasp of the language. But as I’ve been doing a little more reading/thinking, I’m guessing that there was a time period that Maori had no role in the traditional school. It seems that there is always that battle of assimilation – how much a group has to give up to fit in. I think, in some ways, that rocky period might be over, and there has been resurgence in the use of Te Reo in public settings – radio stations, a tv station, and speech-making competitions for youth.

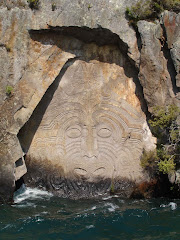

I imagine that Maori people were at one time discouraged from practicing their language and culture. As Europeans settled in New Zealand in increasing numbers, Maori people remained in rural areas. Families and their extended kin, the hapu (sub-tribe), remained strong because Maori people lived near each other, using their language and practicing traditional customs. Slowly though, like the industrial revolution in the US, the bulk of the Maori population has shifted to larger urban areas for work opportunities. This movement seems to have weakened the hapu and thus decreased the use of Maori language and customs.

New Zealand is still a relatively young country, and New Zealanders, both of European, Maori, and other descent, are really still sorting things out. As the election in the US progressed, both Cory and I fielded a lot of questions about racism in America. (I’ll save that and a report on some of the other impressions of American that are held here.) But while it is an uncomfortable subject, one that neither of us have ventured to bring up with any Kiwis here, there is some lingering racism here in New Zealand.

The Treaty of Waitangi officially created the republic of New Zealand. It was a document signed by leaders of European settlers and leaders of (some) Maori tribes. The document was written in English and then translated into Maori. The translation was difficult, and both groups came away with different understandings of what had been agreed to. As a result, there are still ongoing disputes over areas of land. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up to resolve these disputes, but the claims are many and the progress is slow. Land that had been usurped by settlers has, at times, been returned to the iwi (tribe) that once ruled it. As you can imagine, this has not always gone over well with the non-Maori of the area.

But, as problem-fraught as the situation is, you have to hand it to the Kiwis. They are working hard to maintain the identity and offer fair treatment to the various cultures that call New Zealand home.

And, now, back to the point… There seems to, then, have once been a period when Maori language was not commonly spoken, which has lead to our classmates’ lack of knowledge and current desire to learn. The positive for us is that the class has moved slowly, focusing so far on pronunciation and greetings. There is an important and fairly extensive greeting, which identifies to listeners the places that are important to you (mihi) and outlines your family genealogy (whakapapa). On our last night of class, we will be offering our introduction to the elders of a local iwi. It is something I am actually very nervous about, as it feels as if it is a presentation of oneself, and I’d like to do it well. I’ll leave you with a transcript of my mihi; I’ll save my whakapapa for another day!

Ko Honda te waka/ My canoe is Honda

(You should put the name of the boat that brought you to the land; the Maori people arrived in New Zealand in sea-going canoes and can name the waka that brought their descendents.)

Ko Pilots Knob te maunga/My mountain is Pilots’ Knob

(Really, what mountain does a girl from Iowa identify with?)

Ko Mississippi te awa/ My river is Mississippi

(At least this one was easy.)

Ko te kainga te marae/My meeting place is my home

(This is one that doesn’t have a good fit, but iwis and hapus have a meeting place that is very important and steeped in history. Some classmates have listed their church in this place as well.)

Ko Amerikan te iwi/My tribe is American

(It sounds weird, but it’s accurate.)

Ko Payne te hapu/My sub-tribe is the Payne family

Ko Erin toku ingoa/My name is Erin

Thursday, November 6, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment